Throughout 2025, Pilobolus brought movement to stages, classrooms, and unique community spaces through performance, education, and creative partnerships. As a nonprofit organization, this work was made possible by the support of our donors, and continued support ensures that this work continues to thrive in the years to come.

Here’s a look back at some highlights from 2025…

PERFORMANCE & NEW CREATION

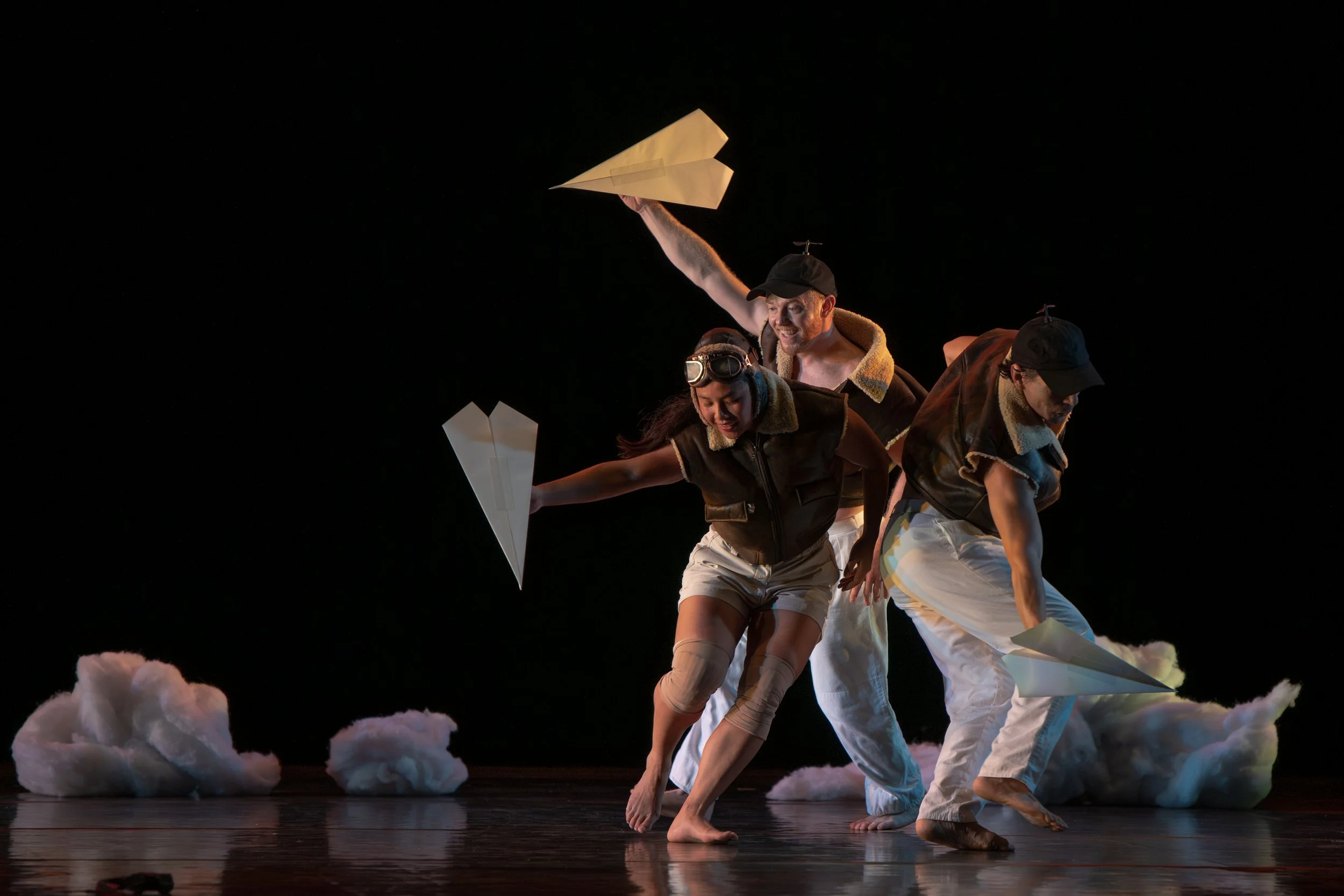

Other Worlds Collection debuts at Joyce Theater Residency in NYC, including two new works

Pilobolus returned to The Joyce Theater in New York City for a three-week residency, premiering the Other Worlds Collection. Two significant new works made their NYC debuts: Flight—a piece inspired by founding company member Lee Harris—and Lamentation Variations, Pilobolus’s interpretation of Martha Graham’s iconic solo Lamentation, created in celebration of the GRAHAM100 and Lamentation Variations Project. (Fun fact: Flight provided the creative runway for the new kids’ show Flight School!) The residency also included classics and recent favorites in repertory, a children’s matinee, a curtain chat with Clinton Kelly, and a unique patron walk-on in Walklyndon.

Opening Penn & Teller’s 50th Anniversary Show at Radio City Music Hall

Pilobolus was honored to open Penn & Teller: 50 Years of Magic at Radio City Music Hall. The partnership reflects a continuing creative relationship.

Alternative Performances Delight New Spaces

Pilobolus presented an immersive event titled Microdose with Pilobolus at farm.one in Brooklyn, NY. Attendees experienced pop-up spectacles, sensory delights, and performances in an alternative, participatory setting. This experience inspired the creation of a new adults-only cabaret show, which debuted at the Mahawie Performing Arts Center’s new Indigo Room in Great Barrington, MA, and which will continue to grow in 2026—stay tuned!

Pilobolus + Lorelei Ensemble Collaborate on love fail

Pilobolus’s collaboration with Lorelei Ensemble debuted love fail at Denison University’s Vail Series in Granville, OH. The work combined Pilobolus’s choreography with Lorelei Ensemble’s vocal performance, presented by a quartet of dancers performing alongside the choral singers.

EDUCATION & COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Adult Winter Intensive at Jacob’s Pillow

Pilobolus held its first Winter Intensive Workshop for adults at Jacob’s Pillow in Becket, MA. The weekend experience brought participants together with Pilobolus’s artistic leadership and teaching artists to explore creative and collaborative movement. Based on the success of this program, Pilobolus will return to Jacob’s Pillow in January 2026 for another weekend workshop.

Educational Partnerships and Growth

Pilobolus announced a multi-year educational partnership with the Saratoga Performing Arts Center (SPAC) to co-create a nationwide education program. The initiative launched with an intergenerational pilot workshop at Skidmore College that brought older adults and college dance students together to explore creative problem-solving, experimentation, and teamwork through movement led by Pilobolus teaching artists.

Our work with students of all abilities was highlighted with our partnership with CATA’s Moving Company, a mixed-ability dance ensemble in Great Barrington, MA. Pilobolus teaching artists Emily Kent and Derion Loman collaborated with CATA artists in weekly movement sessions leading toward celebratory performances scheduled for May 2026. This is just one of the myriad educational experiences Pilobolus facilitated throughout the year, including moving with students at Greater Hartford Arts Academy, Taft School, Chance2Dance, Washington Senior Center, Fight Cancer Like a Dancer, and more.

We also launched three new class offerings:

Kids Class Series for children ages 7–11, using movement games and creative prompts to explore collaboration and physical literacy.

Pilobolus Continuum for ages 13 and up, an intergenerational class where participants explore movement together regardless of prior dance experience.

Bounce Back for older adults to build confidence, balance, and mobility through gentle movement and balance exercises.

These classes brought Pilobolus’s movement philosophy into local community spaces and expanded access to creative movement for all ages.

Pilobolus also returned to Dartmouth College for the celebration of the newly redesigned Hopkins Center for the Arts. Activities included Connecting with Balance and the Pilobolus Alphabet Dance Workshop, immersive site-specific performance throughout the building, and collaboration with the Dartmouth Dance Ensemble.

WHY SUPPORT PILOBOLUS MATTERS

Pilobolus’s performances, new work, educational initiatives, community classes, and collaborative programs all depend on contributed support. Donor generosity sustains touring, teaching, creation, and outreach efforts that bring movement into communities, classrooms, and stages across the USA and the world.

Your support helps make this possible. If you value the experiences Pilobolus shared in 2025 onstage, in studios, and in your backyard, please consider making a donation to ensure the work continues into 2026 and beyond.